New Zealand's largest city sits on a field of 53 identified volcanoes. What happens when the 54th erupts?

James Ball

DISCLAIMER: This is a scenario for a fictional eruption of the Auckland Volcanic Field.

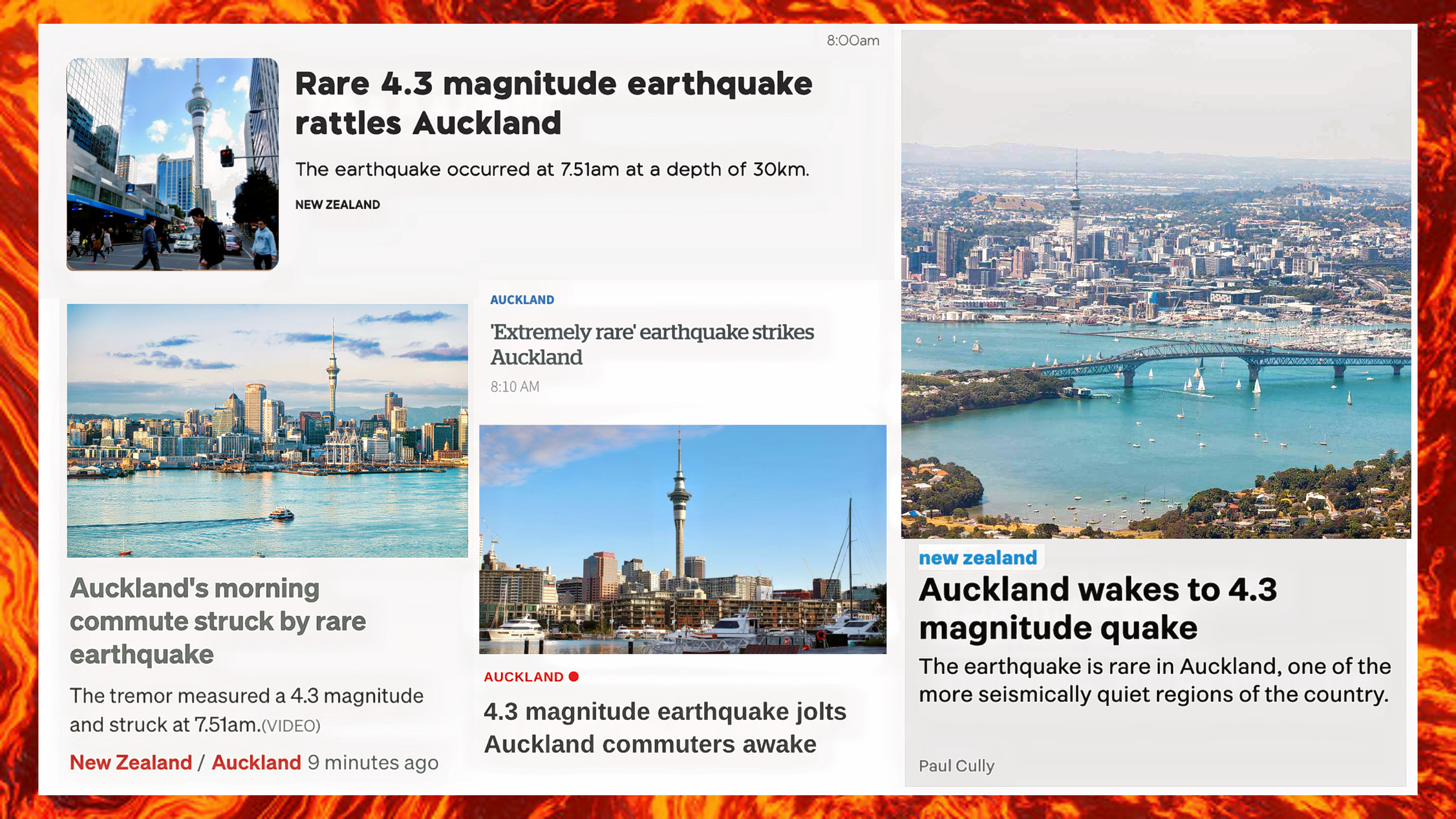

For many Aucklanders, it was the first time that the ground beneath their feet had betrayed them. Straddling a narrow strip of land flanked by two harbours, Auckland is home to 1.7 million people — a third of New Zealand’s population. Living in a seismically quiet region of a country caught in a tug-of-war between tectonic plates, they had grown complacent. But nature is patient, waiting for the perfect moment to remind us of its power.

Pedestrians, clutching their takeaway lattes as they trudge up Queen St., feel the tremor, a passing sensation that could be mistaken for ongoing construction. Cars parked on clogged motorways rock on their suspensions. An office worker on a Britomart-bound train blinks in confusion, attributing the slight jolt to fatigue. Most dismiss the tremor, but some see it for what it is: a sign that something bigger is coming.

After six centuries of dormancy, the Auckland Volcanic Field is stirring, and it will deliver a wake-up call that the city will not soon forget.

From a young age, Thomas Stolberger has been fascinated with rocks and volcanoes, following his passion for Earth’s natural wonders by studying geology and geography during his school years. This proved to be a rock-solid foundation for his current role as a senior researcher at the Determining Volcanic Risk in Auckland research program, known colloquially as DEVORA.

“A lot of the work that DEVORA does is all about determining how the field behaves and what we might expect, and then we use that to inform policy and decision-making when it comes to the Auckland Volcanic Field,” said Stolberger.

Beyond this primary mission, DEVORA conducts research exploring the extensive impacts of volcanic hazards on critical infrastructure, delving into the complexities of disaster law, and incorporating the insights of mātauranga Māori into their scientific framework.

But to look forward, you have to look back.

Kauri trees and branches are preserved forever in basalt at Takapuna Beach. PHOTO: James Ball

Kauri trees and branches are preserved forever in basalt at Takapuna Beach. PHOTO: James Ball

Boggust Park Crater, one of the four new volcanoes discovered in South Auckland in 2011.

Boggust Park Crater, one of the four new volcanoes discovered in South Auckland in 2011.

In their current roles as parks, coastal defence sites and stadiums, Auckland's volcanoes have a number of diverse uses. Yet, beneath these functions lies the unifying factor of their monogenetic nature, where each volcano only erupts once.

Stolberger describes each eruption as “a little bubble of magma that bursts at the surface” and that “the next eruption will come from a new bubble.”

“A lot of the time people will ask ‘I live near such and such a volcano, when is that gonna erupt again?’ And the truth is, that volcano will not erupt again, but another bubble of magma could appear nearby, or it could appear kilometres down the road. They're not linked in that sense, but they're all part of the same field.”

The youngest of Auckland’s volcanoes is also far and away the largest. Rangitoto Island rose out of the Hauraki Gulf about 500 years ago and comprises a little over half of the volume of the field alone in terms of eruptive material. It was the first time that a volcanic eruption in Auckland was witnessed by humanity, but it will not be the last.

What can we expect from a new volcanic eruption in Auckland?

Thomas Stolberger, Senior Researcher at DEVORA. PHOTO: James Ball.

Thomas Stolberger, Senior Researcher at DEVORA. PHOTO: James Ball.

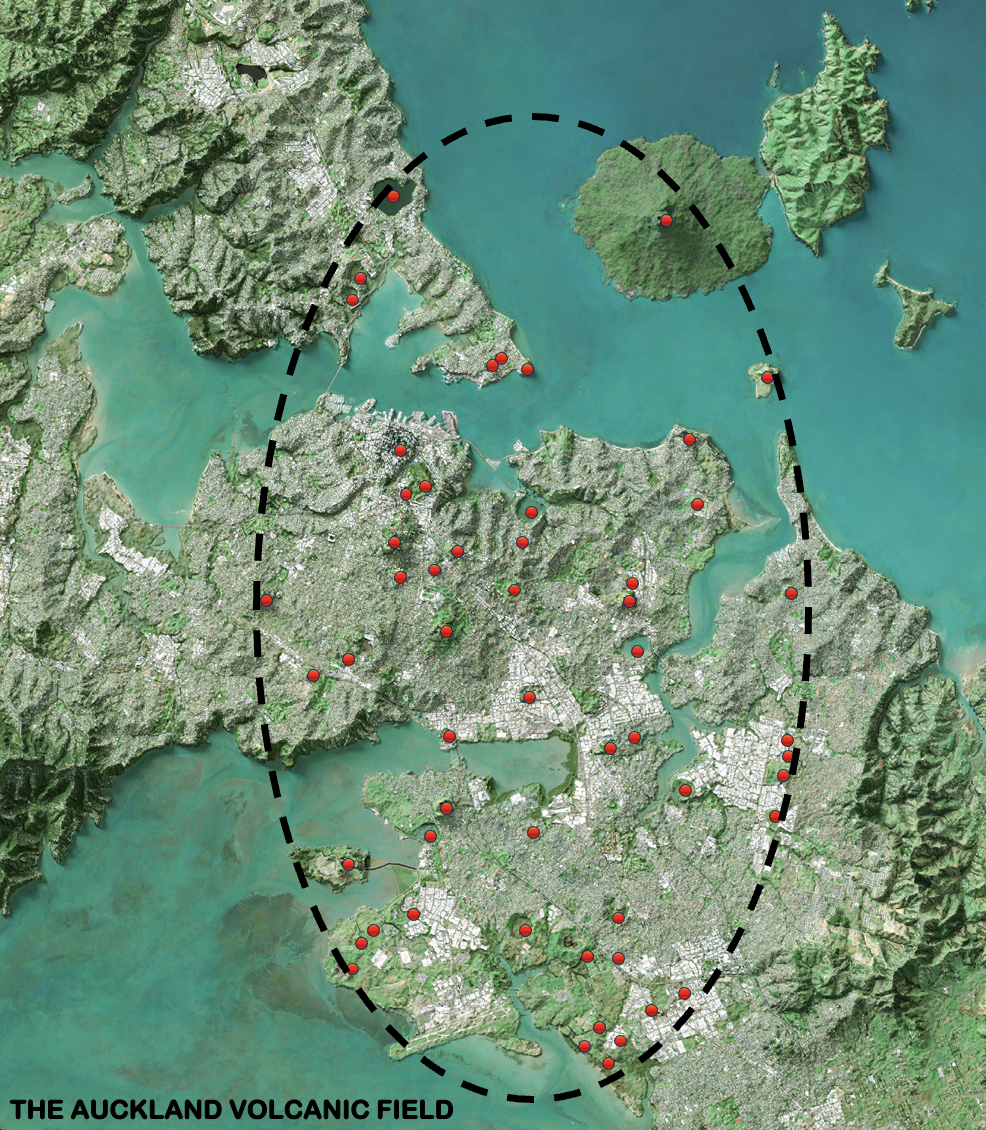

A map of the Auckland Volcanic Field.

A map of the Auckland Volcanic Field.

Auckland’s first eruption took place around 193,000 years ago. The Earth was in the grips of an Ice Age, which meant that sea levels were far lower than they are today. The Waitematā Harbour was at this point, a lush, forested valley. Lava flows from the Pupuke Volcano crept into these surrounding forests, sparking massive forest fires. These lava flows entombed some kauri trees and branches, the remnants of which can be seen today in basalt deposits at the northern end of Takapuna Beach.

The Auckland Volcanic Field underlies much of the city, from Takapuna in the north and Wiri in the south, and Mount Albert in the west to Howick in the east. So far, it comprises 53 volcanoes.

“I say ‘so far’ because we’re still finding new ones,” said Stolberger.

“There's a real potential that there could be some buried ones or hidden ones under other volcanic features, or even under the harbour that we don't know about yet.”

New volcanoes have been discovered as recently as 2011, when five new centres were identified across the city at Grafton, Favona and Wiri.

At the time, geologist Bruce Hayward said that they had not been previously recognised because they are not major landform features like many of Auckland´s volcanoes.

“Fortunately, all four craters are protected within reserves and can now be cherished and managed as part of Auckland´s rich volcanic heritage — unlike many of the volcanoes that have been quarried away or buried beneath subdivisions in this part of Auckland over the last 60 years.”

The anonymity of these craters may have saved them from being cannibalised by a growing Auckland. While several volcanoes are hidden beneath the urban landscape, some bear the scars of its construction.

Many thought that the first earthquake was a one-off, that it was a seismic anomaly. Boy, were they wrong. On Day 1, sixty earthquakes at a depth of 20-30km shook Central Auckland and the North Shore. The Auckland Volcanic Field Alert Level is raised to 1 for the first time ever, indicating unrest. On Day 2, the number of earthquakes triples and the depths shallow to 10-20km. 204 earthquakes rattle the city, centring on the CBD but extending as far as Mount Albert and Takapuna. Day 3 reveals a pattern, arcing around Waitematā Port and between the CBD and Devonport. Speculation rippled through Auckland with each tremor. Could this activity mean the reawakening of the volcanic field? As the city continues to quiver and tremble, a particular scientific discipline finds itself in the spotlight.

In East Auckland’s Point View Reserve stands a strange sight: a massive windowless concrete structure, about the size of a rugby field. It looks like a bunker that might be used to survive the apocalypse, but in reality, it might help Auckland predict a volcanic one.

Encased within its solid confines is a seismograph — one of eleven installed around the region, and a vital instrument in the toolbox of GNS Science’s experts, including Brad Scott, who possesses decades of experience in volcanic monitoring.

Usually, there are three methods used by experts to monitor volcanic activity, said Scott.

These are monitoring seismic activity, tracking ground deformation, or studying geothermal systems.

In Auckland, eruptions occur at a new location of the field each time, making the monitoring of seismic activity the only applicable technique.

Unlike traditional volcanoes such as Ruapehu, Ngauruhoe or Whakaari/White Island, where monitoring is able to be centred on a fixed geographic point, Auckland’s volcanic landscape presents a challenge.

“We don’t have a dot on the map to monitor, we have a broad geographic area where something may happen," said Scott.

“The real key for all kinds of monitoring, regardless of the technique is to develop an understanding of the normal background activity, and then you can try and identify deviation from that.”

Monitoring in Auckland hasn’t always been as instantaneous as it is today. In the past, technicians at power stations used paper records to measure seismic activity.

“They got taken to a university or to Wellington and processed, and then you got an earthquake result a week or a month later.”

Digitising the seismic monitoring network has allowed GNS Science to streamline the process significantly.

“The computer system received the data, analysed the data if an earthquake occurred, had a go at locating the earthquake and printed out a result in under a minute from memory.”

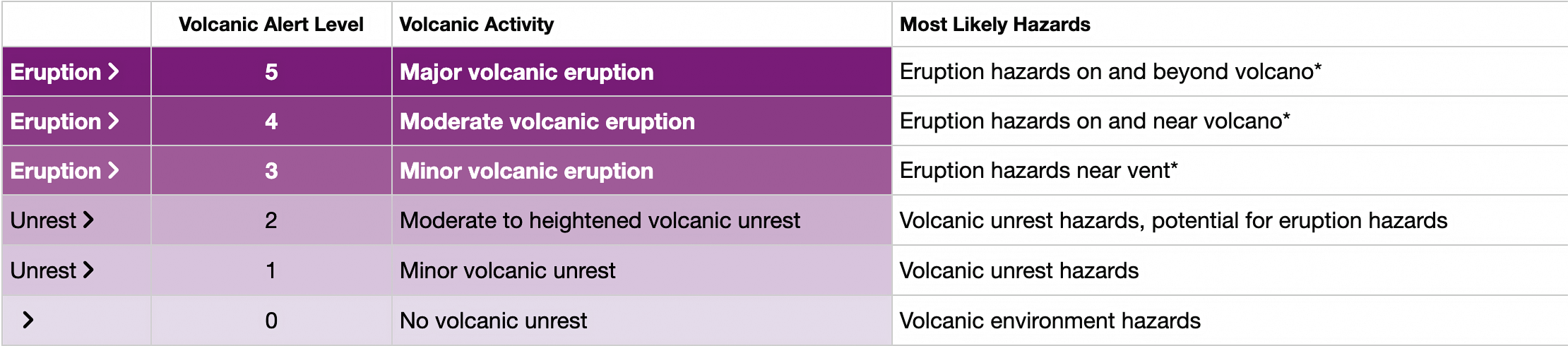

These results will help GNS Science to set a Volcanic Alert Level for the Auckland Volcanic Field. Based on six levels, the system is intended to describe the current status of an active volcano. That information is then communicated through a volcanic activity bulletin (VAB), which is available to the public, the media, responding agencies and the government at all levels.

“Everybody gets the same information at the same time and that then kicks in response mechanisms,” said Scott.

But how exactly do experts ascertain volcanic activity from earthquakes?

PHOTO: James Ball

PHOTO: James Ball

An eruption at Mount Ruapehu in 1995. (Source: Te Ara)

An eruption at Mount Ruapehu in 1995. (Source: Te Ara)

Geonet's Volcanic Alert Level system.

Geonet's Volcanic Alert Level system.

As the earthquakes shallow and cluster around the Waitematā Port, scientists make the call that Auckland’s 54th volcano will erupt somewhere in its vicinity. The order to evacuate is issued, encompassing a 5km radius of the likely vent location. The Volcanic Alert Level is upgraded to Level 2, indicating moderate to heightened volcanic unrest. There’s not much time left. At the break of dawn on Day 4, cracks begin to appear in the concrete and steam starts to discharge from the harbour. The magma is nearly at the surface. The mass exodus from Auckland’s central suburbs begins, a city in motion, racing against the forces of nature. The hours tick away, and the urgency of the situation grows with every second. At this pivotal moment, emergency management teams take centre stage, their expertise and preparation the last line of defence.

Auckland’s Emergency Coordination Centre is one of the most colourful workspaces I’ve ever seen. Blue, orange, yellow, or red placards crown every workstation, but their purpose is far from aesthetic. Instead, these colours assign and distinguish roles that could be the key to saving lives in emergency situations. This workplace is Auckland’s main hub for emergency management, where the vivid colours denote various roles and responsibilities.

Angela Doherty’s role is principal science advisor, a job that marries her two great passions: geology and public service. Over her shoulder is a screen displaying the Geonet website, which shows the current Volcanic Alert Levels for active volcanoes across the motu. The Auckland Volcanic Field is currently at Level 0, indicating no volcanic unrest. It’s never been upgraded.

Doherty said that the hardest part about an eruption is understanding where it will be, and that is not known until it is almost imminent. To navigate this uncertainty, Auckland Emergency Management collaborates with scientists to create scenarios that simulate potential eruptions.

“We look at the scenarios that the scientists have helped us create to play out that event, almost as a serious game, to decide exactly how any eruption could impact our communities in different ways.

“What we have to do and the best way to prepare ourselves for these events is to actually give ourselves options.”

The approach focuses on providing a range of options for response, given the unpredictable nature of eruptions.

Auckland boasts over 50 civil defence and community evacuation centres, strategically located across Tāmaki Makaurau. The decision to activate these centres depends on the eruption’s actual location and the number of people requiring evacuation.

“We also know from previous events in the recent past in Auckland that the Auckland community is really good at supporting itself, so we have access to a wonderful range of community groups that stand up in emergencies to support their local area as well.”

In times of emergency, AEM leverages two main channels of communication.

First is the emergency mobile alert, reserved for when there is an imminent threat to safety.

“We’ve had a few emergency mobile alerts in the last few years,” said Doherty.

“We’re all familiar with how it blows up your phone and causes a big ruckus, and it can be tailored to a specific region.”

AEM also has established agreements and protocols with a wide range of media, ensuring information dissemination through various channels.

Auckland is one of the most diverse cities in the world.

While this would normally be a strength in many respects, Doherty said that it can be a challenge when it comes to communicating emergency information.

“We’ve got lots of people that English is not their first language, we’ve got people with difficulty understanding verbal communication, people that don’t have access to cell phones.”

Using a variety of channels is essential in ensuring everybody is contacted effectively, Doherty said.

Volcanic hazards can also have a range of impacts on Auckland's critical infrastructure.

While it is a very low risk of an eruption happening in the Auckland Volcanic Field, the impacts could be potentially catastrophic, making it something AEM needs to pay attention to.

“What we try to focus on at Auckland Emergency Management is just building people’s hazard literacy and also personal resilience of their homes, workplaces and communities.

“The best thing people can do is create a family emergency plan.

"It works for any and all events, including volcanic eruptions, and always listen to advice from the sources of truth in an eruption, like Auckland Emergency Management, GNS Science and the National Emergency Management Agency who will be all doing our best to shepherd people through what's probably going to be an extremely scary experience for all of Auckland.”